At the end of the apartheid era, South Africa looked to the United States for guidance in creating a new democracy.

Key figures like activist and lawyer Albie Sachs helped draft a constitution that incorporated American principles while establishing new forms of constitutional democracy.

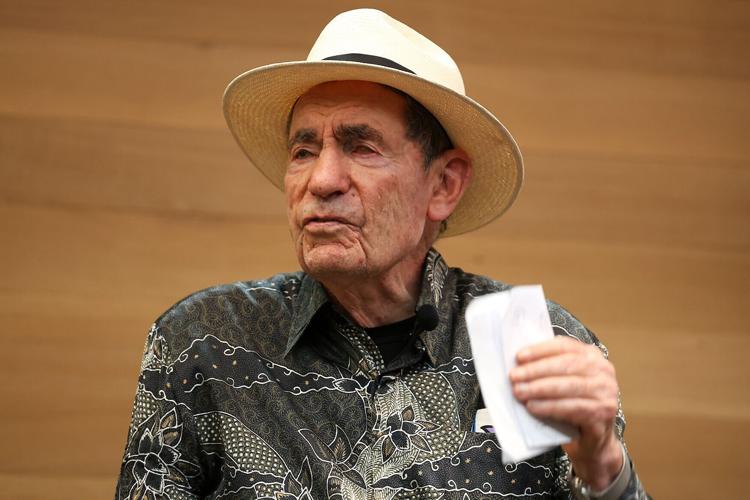

This firsthand experience in the creation of a modern democracy made Sachs a fitting first speaker for the Kinder Institute’s “America at 250” event. The event brings international speakers to Columbia for a global perspective on constitutional democracy.

Sachs addressed a full house Tuesday evening at the State Historical Society of Missouri, comparing the 250-year history of the United States to his own experiences with South Africa’s transition to a constitutional democracy.

Sachs’ activism with the African National Congress led to his arrest three times, as well as torture and exile. An attempt on his life motivated him to help draft a new constitution for South Africa and return to his home country after 24 years.

He became a leading advocate for the inclusion of a bill of rights and an independent judiciary, both later adopted by the new parliament. Nelson Mandela appointed Sachs to the newly established Constitutional Court in 1994, where he served for 15 years.

During his lecture, Sachs outlined three constitutional models South Africa considered when drafting its own.

The first, like the American Constitution, establishes governmental structures and limitations. The second seeks to unite progressive forces to transform the country, and the third establishes a multi-party democracy and requires the government to bring about change.

South Africa adopted the third model but added a requirement for power sharing between parties to ensure racial equality. One proposed solution — a rotation of three presidents — was rejected, he said.

“It would have been an absolute disaster,” Sachs said.

The answer was a bill of rights, and he credited the United States for the idea.

“This idea of certain fundamental rights that went with citizenship resided in people simply because they were people.” Sachs said. “It’s protecting human beings.”

The same held true when establishing the judiciary. The Constitutional Court, unlike the U.S. Supreme Court, aims to manage division and opposition rather than simply deciding a winner. Sachs says the combined function of these is vital to democracy.

“You see, what we owe to the U.S. of A. (is) that very theme of fundamental rights,” he said. “And fundamental rights require structures, separation of powers to ensure the government doesn’t deny people their fundamental rights,”

The Kinder Institute’s “America at 250” series will continue with lectures by Tamson Pietsch, director of the Australian Centre for Public History at University of Technology Sydney, and Mario Del Pero, professor at the Centre for History at Paris’ SciencePo.

The lectures will be held at 5 p.m. in the Tiger Hotel on Jan. 30, with the option to attend virtually.