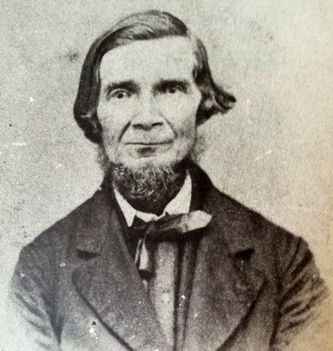

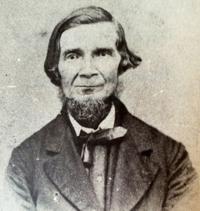

Life along the Big River in those early years when pioneers were settling the wilderness was hard, basic and wild, but a few strong leaders like Amandus Crull brought civilization with them.

Crull, a German immigrant who came to Big River Township in 1841, was a farmer who became a physician and wrote prolifically, penning a regular column for a St. Louis newspaper, a couple of autobiographies and articles for the Jefferson Democrat, according to the book, Dr. Amandus Crull, of Jefferson County, MO, published in 1992 by his great-grandson, Albert J. Crull.

When Crull first came to Jefferson County in 1841, there were only two other German families who had settled west of the Big River “to the best of his knowledge,” according to Goodspeed’s History of Jefferson Co., MO, published in1888.

He arrived in the U.S. in 1838, from Mecklenburg, Germany, at the age of 18. He was college educated, fluent in French, Spanish and, of course, his native German. He took a tour of several major cities and had relatives in St. Louis County, which led him to move to nearby Jefferson County. He settled in Big River Township and married Mary Ann McFry of Franklin County who was 15 at the time. They lived, at first, near Belew Creek in the Hillsboro area, but later moved to Morse Mill and farmed along the Big River with their two children – John and George, according to the 1860 U.S. Census.

Goodspeed’s history, however, says that a few years before the Civil War, Crull began studying medicine, and in 1861 began his practice.

By the time Crull was 50, he had lived most of his life in Jefferson County and shared his observations of life in the Big River Township in the 1840s in an article titled “On Big River 30 Years Ago” published in the Jefferson Democrat in October 1870.

The area, at the time, was a farming community and apparently families lived by working with their hands and bartering with their neighbors.

“Corn-shuckings, log-rollings, harvesting..., were leading features of the day. No one thought of hiring or of paying wages,” Crull wrote.

He drove home his point with an anecdote.

“The scarcity of money in those days may be forcibly illustrated by the statement that when George Dugge received a letter from Europe, he had much difficulty in procuring sufficient funds with which to pay the postage. The amount was twenty five cents. It was found, after thorough search, that the amount could not be raised in Big River; so Dugge was compelled to take a trip down to the Meramec in order to borrow the sum and pay the postage on his letter.”

Crull said the people of the times, in the 1840s, were quite friendly and helpful to their neighbors for the most part but had their own way of dealing with disputes.

“One of the peculiarities, I might say eccentricities, of the time was the manner in which disputes and difficulties were almost invariably settled, which was, by a rough and tumble fist fight; after the fight occurred, neither due grudge or ill-feeling was harbored by either of the former belligerents, and the victory of one over the other was a vindication of the justice of his cause and correctness of his position,” according to the article in the Jefferson Democrat.

The people worked hard and needed little, especially in the case of a neighbor Samuel Herrington, he noted.

“He has been known to work for hours upon an old gun or plow and would take nothing for payment. He had also certain peculiarities and oddities, all his own. For instance: His family lived for thirty years in an open cabin on the river bank. No door was visible,” he wrote.

“At last his wife prevailed upon him to make a door of boards. It was found so inconvenient and its use so impractical, that Uncle Sam threw it into the river, lamenting that he had wasted so much time and labor upon it.”

By 1876, Crull and his wife were living in what was then known as Dittmer’s Store (now Dittmer), where they remained for the rest of their lives, according to the Jefferson County Missouri Historical Atlas.

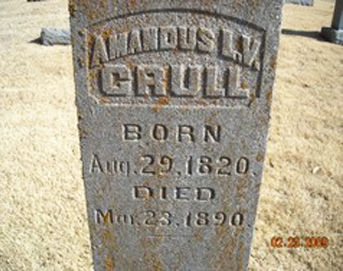

Both Crull and his wife died within two months of each other in 1890. Mary, who was not in good health, went to visit her son on “a stormy day” and developed pneumonia. She died that January. Amandus took ill the same time as Mary and couldn’t visit her on her deathbed. He died in March of that same year at the age of 70, according to the Jefferson Democrat. They are both buried in the cemetery at Cedar Hill Baptist Church in Cedar Hill.

Members of the Crull family, six generations later, still live in Dittmer today. Amandus’ sons took over the Morse Mill farm, said Mary Kley, 92, who married Amandus’ great-grandson, Floyd.

“The farm is still there as far as I know,” Kley said.

The family, however, moved to Cedar Hill when Arthur Amandus’ grandson was 8, she said.

Mary’s and Floyd’s sons, Floyd Jr. and Charles Crull, and her grandsons farm today in Dittmer on 170 acres that straddle the Jefferson/Franklin County line.

Send submissions to LOOKING BACK to nvrweakly@aol.com or bring or mail them to the Leader office, 503 N. Second St., Festus (P.O. Box 159, 63028). Please include your name, phone number, a brief description of what’s in the photo and tell us how you came by it. Please also include when it was taken, where and by whom (if known). A new LOOKING BACK photo will be posted each week.