Nearly 94 years ago, the Sulphur Springs train wreck on Aug. 5, 1922, splashed a horrific and gripping tale across the pages of Jefferson County history. Although a living memory of the disaster is gone, Helen Mathena, 85, formerly of rural Festus, heard the story many times from her mother, who was on the train that fateful day.

Thirty-four people lost their lives in the crash and another 186 were injured when Express No. 4 slammed into the back of Missouri Pacific’s Local Train No. 32, according to “Remembering Missouri’s Worst Train Disaster,” a slide presentation by John Abney.

Mathena’s mother, Esther McDonald, then 18 and of Crystal City, was the only passenger in the last car of Local Train No. 32 to survive, Mathena said.

“They laid her out with the dead,” Mathena said. “Then someone noticed that she was breathing.”

McDonald, her next-door neighbor, Irene Moon, 17, and McDonald’s cousin, Alice Cooper, 36, of Festus, had transferred from the Mississippi River and Bonne Terre railroads and boarded the Local Train at Riverside Station. They were heading to St. Louis and planned to go to the Highlands, an amusement park in St. Louis Forest Park the next day, a Sunday.

“My mother was a Christian, baptized at First Baptist Church (Festus-Crystal City),” Mathena said. “She always felt like she shouldn’t be going to the Highlands on a Sunday.”

The Local Train was behind schedule that day and stopped to take on water from the tower in Sulphur Springs just after 7 p.m., according to a New York Times article.

Some of the passengers got off the train to walk along the tracks. The sun was beginning to set, and the passengers were enjoying the colorful sky and its reflection in the ripples of the Mississippi River below, the Times reported.

Express No. 4 out of Fort Worth, Texas, was on time that evening and, unknown to anyone, was about four miles behind the Local, bearing down on the train at about 45 mph.

It is believed that Matthew Glenn, engineer of the Express, was reading orders he had received at the Riverside station and missed the red signal that indicated the track ahead was blocked.

Irene and Alice were seated facing the rear of the train in that last car when at 7:17 p.m., Express No. 4 rounded a curve in the track and came into view.

“My mother always wondered whether one of them (the two women she was with) saw the train coming,” Mathena said.

Others did see it.

“Dashing around the curve came the limited train. A shout. A man rushing down the track by the halted Local shouting a warning. Then there came the grinding of the brakes of the oncoming train, cries, and almost immediately a crash,” the Times reported.

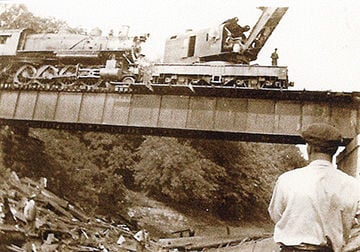

The last four coaches, which were sitting on the trestle over Glaize Creek, were knocked off the track and fell 40 feet off the trestle and down the embankment. The locomotive pushed its way through half the train and came to rest on the trestle, according to the Times.

Rescue efforts began as night descended. Dr. W.W. Hull of Sulphur Springs was the first doctor and for some time the only doctor on the scene.

The coach McDonald and her companions were in was little more than a pile of splintered wood lying in Glaize Creek. Cooper died in the crash. Her brother, Wendell, rushed to the scene and found her in the creek, according to Abney.

Moon died that night too.

“When they brought Irene’s body home, her sister (Gertrude LaRose) dropped dead of a heart attack,” Mathena said.

The family held a double funeral and burial for the sisters.

“Esther learned of this some time during her recovery and received a picture of her friends’ grave,” Mathena said.

When they pulled Esther McDonald from the wreckage, she was unconscious and would remain unconscious for the next two weeks. She had a crushed pelvis and broken collar bone. The bridge of her nose was crushed, her eye was dislocated from its socket and lay on her cheek, Mathena said.

“She spent four months in the hospital,” she said.

Fortunately, her eye was returned to its socket undamaged and her injuries healed. But the blue spots on her body, places where cinders along the track were ground into her skin remained as reminders of the accident for years.

McDonald, although older than the other students, went back to Festus High School and graduated. She taught at Zion School in Mapaville and met James “Allen” Whitehead at a picnic where she had been invited to sample watermelon grown on his family’s farm. They were married in 1929, and the couple had two children, a boy and a girl.

McDonald suffered some health problems as a result of her injuries – headaches caused by her damaged sinuses, and short “nervous spells” where McDonald was unable to move, speak or otherwise respond for periods as long as 30 minutes, which were later diagnosed as seizures, Mathena said.

The train wreck, her injuries and the loss of Moon and Cooper, however, were just a few of the many losses in her mother’s life, Mathena said.

“Her parents moved the family to Montana when she was young and her younger brother died of pneumonia there,” Mathena said. “They brought the family back to Jefferson County and it was not long after when her older brother died of pneumonia.”

Esther was her parents’ only surviving child.

Then in 1958, her son, Jim, at age 21, was one of three people killed in an auto accident on Hwy. 61-67, Mathena said.

Mathena and her husband, Troy, had moved to Irving, Texas, and as her mother and father got older, they joined the Mathenas there to be close to their grandchildren.

Despite the challenges of her life and the memories that haunted her, McDonald lived to see her 93rd birthday and died in 1997.

She and her husband, Allen, are buried in Zion Methodist Cemetery in Mapaville.