There are names that stand out in history. Very few haven’t heard of William Clark, the explorer who with Meriwether Lewis and the party of Discovery crossed the great span of the Louisiana Territory and claimed the Pacific coast for the nation. Clark later went on to become the governor of the Missouri Territory.

Other less-known members of his family also had an impact in the country and the state. One of them, Benjamin O’Fallon, lived in Jefferson County. O’Fallon was not only an Indian agent but also a patron of the arts.

Dr. James O’Fallon, who emigrated from Ireland and served as a doctor during the Revolutionary War, married William Clark’s sister, Frances Eleanor. They had several children and one of them was Benjamin, born in 1793. Benjamin lived with the Indians for many years. He was one of the principal partners in the Missouri Fur Co. and became an Indian agent responsible for arranging treaties between the U.S. government and several tribes along the Missouri River, according to "History of Franklin, Jefferson, Washington, Crawford and

Gasconade Counties.”

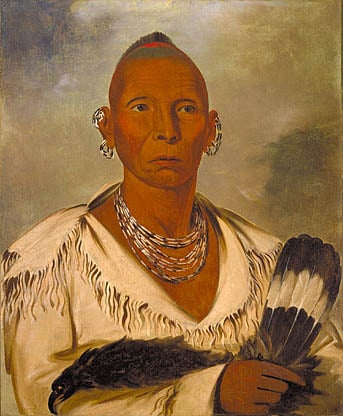

In 1834, he settled in Jefferson County on a tract of land which he called the Indian Retreat Plantation near Sulphur Springs. Through his work with Native Americans, he collected a great number of Indian artifacts. He also developed a large collection of paintings by American artist George Catlin. And in many ways it was O’Fallon’s help that made the paintings possible, according to Selby Kiffer, senior vice president at Sotheby’s, an international art business. Catlin’s goal was to paint the portraits of Native Americans representing each of the tribes in their native costume and build a national Indian Gallery. In the 1830s, Catlin, originally from Pennsylvania, made several trips to St. Louis, his base of operations, and presumably Jefferson County, where O’Fallon lived. The artist was friends with O’Fallon, who often arranged meetings with Native Americans from various tribes and was “one who provided access, assistance and introductions” that furthered Caitlin’s work, Kiffer said.

According to O’Fallon’s daughter Emily, Benjamin was instrumental in Catlin’s work.

“My father assisted Catlin in his troubles among the Indians and by his influence in various ways,” she said. “Otherwise, he could not have succeeded with his enterprise.”

O’Fallon developed a collection of Catlin’s art that numbered 42 pieces. O’Fallon died in 1842. The family kept the collection, until in 1894, Emily decided to find a new home for it. She asked her friend Julia Dent Grant, the widow of the late President Ulysses S. Grant, for advice. Grant alerted a trustee of the Field Columbian Museum, now the Field Museum. Emily sent the paintings to Chicago for inspection. There was a consultation of experts and the endorsement of the chief of the museum’s department of Ethnology and Archeology, F.W. Putnam.

“I think these pictures should be secured if possible. They are of the first importance in regard to

the customs and costumes of the Indians of 50 years ago,” Putnam said.

The O’Fallon collection was especially significant because those paintings featured Native Americans in the West, where many of Catlin’s other painting were done in Europe as Native Americans toured the continent, Kiffer said.

The museum purchased 35 paintings for $1,250.

“The O’Fallon Collection of Catlin’s paintings is most accurately viewed as an embryonic Indian Gallery, contemporary with, and instrumental in, the development of the larger and better-known Gallery now housed at the Smithsonian,” Kiffer said.

Since their purchase in 1894, 30 of the paintings were sold to private collectors in 2004 with the Field Museum keeping the four best, which were offered for sale in 2007.

As for Catlin, his dream of a national Indian Gallery was not fulfilled in his lifetime. He went bankrupt and was forced to sell more than 600 of his paintings. Industrialist Joseph Harrison took possession of the art and artifacts, which he kept as security. Catlin tried to begin again, recreating the collection from outlines of the original paintings. He died in 1872, according to the George Catlin Biography on the website “George Catlin, the Complete Works.”

Send submissions to LOOKING BACK to nvrweakly@aol.com or bring or mail them to the Leader office, 503 N. Second St., Festus (P.O. Box 159, 63028). Please include your name, phone number, a brief description of what’s in the photo and tell us how you came by it. Please also include when it was taken, where and by whom (if known). A new LOOKING BACK photo will be posted each week.