By Stephen Beech

An Antarctic glacier retreated faster than any other in modern history, reveals new research.

Half of the glacier - five miles of ice - disintegrated in just two months, say scientists.

A new study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, details how and why the Hektoria Glacier on Antarctica’s Eastern Peninsula retreated at an "unprecedented" rate in 2023.

American scientists believe the "main driver" was the glacier's underlying flat bedrock that enabled it to go afloat after it substantially thinned, causing a rare calving process.

They explained that Hektoria Glacier is small by Antarctic standards at about 115 square miles, or roughly the size of Philadelphia.

But a similar rapid retreat on larger Antarctic glaciers could have "catastrophic" implications for global sea level rise, according to the study.

Study lead author Dr. Naomi Ochwat, of the University of Colorado Boulder, said: “When we flew over Hektoria in early 2024, I couldn’t believe the vastness of the area that had collapsed.

“I had seen the fjord and notable mountain features in the satellite images, but being there in person filled me with astonishment at what had happened.”

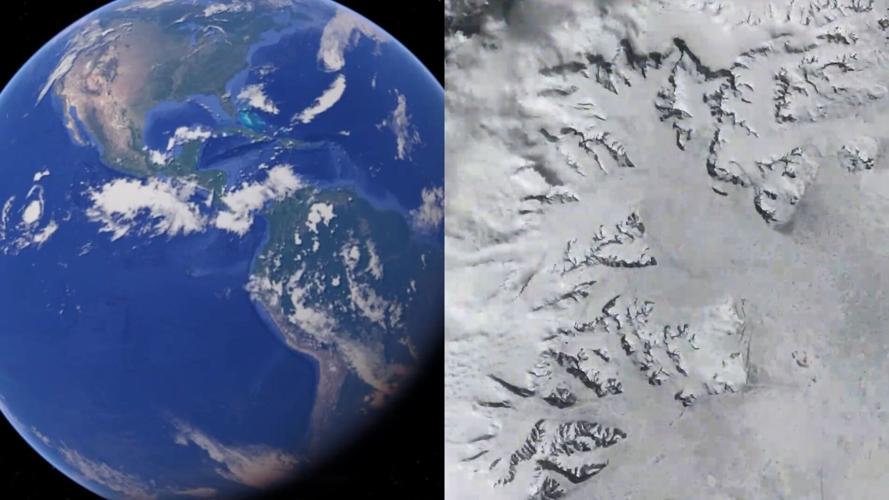

(Cooperative Institute for Research In Environmental Sciences / University of Colorado Boulder via SWNS)

The research team surveyed the area surrounding Hektoria Glacier using satellites and remote sensing for a separate study.

The team wanted to understand why sea ice broke away from a glacier a decade after an ice shelf collapse in 2002.

While analysing results for the first study, Dr. Ochwat noticed data that indicated Hektoria had all but disappeared over a two-month period.

She says that many glaciers in Antarctica are "tidewater glaciers" - ones that rest on the seabed and end with their ice front in the ocean and calve icebergs.

The topography beneath the glaciers is often varied, sitting on deep canyons, underground mountains, or big flat plains.

In Hektoria's case, the glacier rested on top of an ice plain, a flat area of bedrock below sea level.

Researchers had previously found that 15,000 to 19,000 years ago, Antarctic glaciers with ice plains retreated hundreds of meters per day, and that helped the team better understand Hektoria’s rapid retreat.

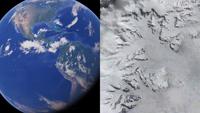

(Cooperative Institute for Research In Environmental Sciences / University of Colorado Boulder via SWNS)

Dr. Ochwat explained that when tidewater glaciers meet the ocean, they can go afloat, where they float on the ocean's surface rather than resting on solid ground.

The point at which a glacier goes afloat is called the grounding line.

Using satellite data, the research team discovered Hektoria had multiple grounding lines, which can indicate a glacier with ice plain topography underneath.

Dr. Ochwat says Hektoria’s ice plain caused a large part of the glacier to go afloat suddenly, causing it to calve quickly.

She said going afloat exposed it to ocean forces that opened up crevasses from the bottom of the glacier, eventually meeting crevasses exposed from the top, causing the entire glacier to calve and break away.

The researchers utilised satellite data to study the glacier at different time intervals and created a detailed picture of the glacier, its topography, and its retreat.

Dr. Ochwat said, “If we only had one image every three months, we might not be able to tell you that the glacier lost 2.5 km in two days.

(Cooperative Institute for Research In Environmental Sciences / University of Colorado Boulder via SWNS)

“Combining these different satellites, we can fill in time gaps and confirm how quickly the glacier lost ice.”

The research team also used seismic instruments to identify a series of glacier earthquakes at Hektoria that occurred simultaneously with the rapid retreat period.

The earthquakes confirmed the glacier was grounded on bedrock rather than floating, proving both the presence of an ice plain topography and that the ice loss contributed directly to global sea level rise.

The research team says their findings may help scientists identify other glaciers to monitor for rapid retreat.

Senior research scientist Dr. Ted Scambos said: “Hektoria’s retreat is a bit of a shock - this kind of lighting-fast retreat really changes what’s possible for other, larger glaciers on the continent."

He added: “If the same conditions set up in some of the other areas, it could greatly speed up sea level rise from the continent.”