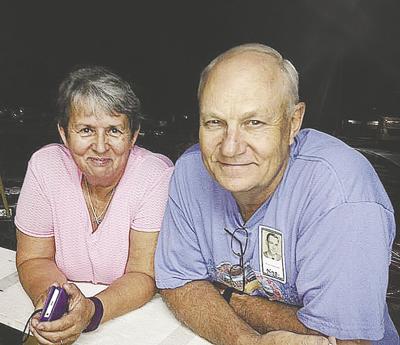

It’s too bad Elaine Simmons has no memory of being a trailblazer.

Simmons, 65, of De Soto was the first COVID-19 patient at Mercy Hospital Jefferson in Crystal City to be treated with an experimental process called convalescent plasma replacement.

Admitted on April 12, Simmons’ symptoms continued to worsen, and she was placed on a ventilator.

As part of an experimental treatment program, she was given plasma, drawn from a person who had recovered from the virus some weeks ago, in order to give her body antibodies to fight the disease.

Simmons’ response to the treatment was immediate and encouraging, and she was discharged on May 4 with the prognosis of a full recovery.

Dr. Karthik Iyer, chief medical officer for the hospital, said he is excited about the potential of this new treatment, although it must continue to be rigorously tested.

“I’d say ‘cautiously optimistic’ is the best way to put it,” he said. “But this has shown enough promise, we are considering it as a first-line treatment now.”

As far as Simmons knows, she could have been given any treatment – or none at all.

“I don’t remember hardly anything from the time I got to the hospital until about a week later,” she said. “They asked my husband about this treatment, and he gave them permission to try. Maybe my experience will give other people hope.”

Familiar faces help

ease the stress

Simmons’ husband of 47 years, Ronnie, come down with the virus in early April, but showed only mild symptoms. Their son, Josh, got sick shortly after his mother and spent several days in the hospital, but never experienced symptoms as severe as hers.

“There’s just so much they don’t know about (the virus),” Elaine Simmons said. “They don’t know why some get it a little and others get it bad. I got a rash for a few days, and they thought it was an allergic reaction. Apparently, it was from the Robitussin they were giving me for my cough. They switched to something else and it went away.”

Simmons said the human element has been an important component of her journey.

“I’m on the road to recovery, and I know it’s because of the excellent care I received,” she said.

“My daughter-in-law, Tracy, is an ICU nurse. Although she couldn’t be my nurse, she was able to visit me, and I remember her holding my hand and talking to me. When I had to start eating food, Michelle Chandler would come in and feed me, because I couldn’t even hold a spoon.

“Without the doctors and nurses and all the people working with me, I guess I wouldn’t be here.”

Simmons said her anxiety level was high when she emerged from the medically induced coma that accompanied her week on the ventilator.

After that, she remembers some of her experiences in the ICU.

“I couldn’t sleep,” she said. “They’d say, ‘Don’t you want to go to sleep for a little bit?’ and I’d say no. I didn’t want to close my eyes because I was afraid I’d never open them again. Then, once I started hearing them talking about how I was getting better, I relaxed and got some sleep.”

Simmons said she suffered some hallucinations, but also had vivid dreams.

“In my dreams, I could hear people praying for me,” she said.

And although she had no visitors, “I could feel the touch of them stroking my hair. That was no hallucination.”

She left the hospital through a parade of personnel cheering her on.

“Then, the day after I came home, they had a parade come through town for me, with police cars and firetrucks and everything. I couldn’t tell you how many cars there were. It was nice to feel so much love and support.”

Simmons gets frequent visits from physical and occupational therapists, and is making steady progress toward regaining her former good health.

“The visiting nurses took blood (May 11), and my doctor is very pleased with all my numbers,” she said. “I’m feeling great, really. I’m still on oxygen, but I’m working to get stronger every day. I’m anxious to get my strength back so I can get out and work in my yard, see my kids and especially get hugs from my grandkids.”

Giving the body a head start

Iyer said Simmons’ successful treatment is one more step toward medical professionals being able to officially add convalescent plasma to their arsenal of weapons against the virus.

“Mercy Jefferson has been approved by the FDA to administer the treatment as part of the National Expanded Access Program through the Mayo Clinic,” he said. “There is a tremendous amount of data being generated at these sites, and convalescent plasma has shown a lot of promise in stopping the progression of the disease. It can decrease the time they spend on a ventilator.”

Iyer said patients must meet certain criteria to receive the treatment through the program.

“They must have a lab-confirmed diagnosis of the virus, be admitted to hospital, and have severe or life-threatening symptoms, or be judged by their health care provider to have life-threatened status,” he said.

“One of the ways people fight infections is developing antibodies, which form in plasma. Once they recover, they can then donate plasma to be given to another individual where it can eliminate the virus from the system.

“The earlier you have access to this and are able to give it to the right population, the more success you might have. Instead of people getting the disease and developing their own antibodies, you are giving them the antibodies already made. You are giving the body a big head start in developing natural immunity.”

Still lots of questions

Iyer said research into COVID-19 treatments is being done along multiple tracks.

“This is a new disease, and we know so little,” he said. “Everyone is out there to get something that can fight this virus. Efforts are ongoing to develop a vaccine, and that’s important. But we need ways to fight it now.”

He said infusing patients with blood plasma has been an effective treatment for other conditions for many years, giving it a head start over new, unproven methods.

“People are willing to try a wide range of different treatment modalities,” he said. “Convalescent plasma is definitely being looked at. It seems to be promising.

“But, we need hard evidence.”

Questions remain about whether patients like Simmons develop antibodies as robust as those who recovered on their own.

“That has to be determined,” Iyer said.

Another question is whether those who recover – with or without plasma treatment – develop immunity against future reinfection.

“The first step in that is getting a reliable test to determine who has already developed antibodies,” he said. “There is a significant population who have been asymptomatic, or who got it mildly and recovered. We would have a significantly larger pool of donors once we have a reliable way to test those people for antibodies.”

Iyer said hospitals have been tracking COVID-19 patients after their release, and will contact them to talk about donating their plasma.

“There are other avenues for people to donate, too,” he said. “If you had it, you should reach out to your health care provider about how you can donate.”

Simmons said she has already discussed the topic with her doctor.

“I definitely will consider donating plasma. You better believe it,” she said. “I won’t hesitate for a moment. I think that may be one of the reasons I’m here now.”

Iyer said new knowledge and treatment tools against COVID-19 are being added almost daily.

“We go off of evidence-based medicine,” he said. “If the evidence is there, it becomes a treatment guideline. Everything we are doing is in the experimental stage now; some things are working, thank God, but there is still a long way to go.

“But I have full confidence in the health care community that we will get there. We have more and more options, and we are winning the battle. Nothing comes with guarantees, but we want to give hope.”